» Hey, you work of art! I would REALLY appreciate it if you could take 5-10 minutes to fill out this survey about this newsletter. It would help me out a ton, and each response guides how I build this community!

This distinction is small but essential to understand: diet and exercise can help manage chronic illness and disability but cannot eliminate them.

Take the Medication

“You can’t solve everything with food.”

My inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) specialist dietician firmly, yet kindly reminded in our appointment this week. “I want to make sure I’m doing everything I can for my health,” I admitted. I was going through a chronic illness flare-up and had found myself depending on ‘safe’ foods to absolve myself of symptoms. She gently reminded me that I had fallen into a common trap of embracing a predatory narrative often forced onto disabled people: that everything can be solved with food. “Food is not medicine,” she explained. “It’s dangerous that disabled people can adopt this narrative and put all the blame on themselves. She explained that diet could potentially help manage some of my symptoms, but it would never cure the root issue. “The right thing to do in a flare-up is to take the medication.”

I felt myself become lighter while the weight of that statement settled into my bones. For weeks, I had been unconsciously forcing myself to eat only the ‘right’ foods, wishing desperately I could cure the infection in my immune-compromised body with air-fried potatoes and de-seeded cucumbers. It had become dangerously close to mirroring my past orthorexic disordered eating habits, of only eating safe foods in an attempt to cure my body of being ‘too big.’ Now, I was trying to will myself away from becoming ‘too disabled,’ as if, in either situation, I had a choice in where my body would ultimately land.

The fallacy of personal responsibility

The narrative that all disabilities are simply a result of us not doing enough to manage our health is a fallacy. Though we are sold the idea that our health is always in our own hands (which coincidentally, makes for great marketing), the body cannot be controlled. Bodies are open systems, affected significantly by many factors, including living situation, geographical location, economic status, genetics, and more. We can attempt to control the size and abilities of our body with diet. Still, in the scheme of the multiple other variables affecting the body’s function, there is never a guarantee that it’s possible.

The online narrative embedded in the ‘health and wellness’ world that managing one's health is solely a matter of personal responsibility is rooted in ableism. It eludes that if you are ‘bloated’ or depressed or even chronically ill, the path to health is quite straightforward. Simply, eat the right foods and do the right kind of exercise all the time, and you will have the capacity to cure yourself. Maybe, just maybe, if you lift weights for an hour five days a week, do a cold plunge every other day, avoid added sugar at all costs, and take $8 wellness shots daily, you will no longer be disabled, fat or sick! You will become invincible and absolve yourself of a range of issues including, but not limited to, bloating, fatigue, migraines, chronic pain and arthritis.

Except… health is rarely that straightforward, especially for disabled and chronically ill individuals. Food is not medicine, and disabilities cannot simply be erased with food and exercise. Of course, diet and exercise is an essential part of managing many health conditions. But, diet and exercise alone cannot cure or absolve someone of a long-term disability. This distinction is small but essential to understand: diet and exercise can help manage chronic illness and disabilities, but it cannot eliminate them.

As such, it is easy to internalize the narrative that if we are chronically ill or disabled, it’s because we are lazy or not doing enough. But this could not be further from the truth. It’s no one’s ‘fault’ for becoming disabled. Not everything can be solved with food. Many bodies in the world need modern medicine to survive and increase our life expectancy, which is the whole point of medicine!

Historical context: the eugenic roots of this narrative

The idea that disabled bodies are undesirable and must be fixed is not new. Anyone remember eugenics? The belief that we should ‘improve’ future generations by eliminating ‘bad’ races and genetics, like disabled people and Jews. By WWI, this idea was supported by most scientific authorities and political leaders. Popular in the early 1900s, this idea was used as an excuse to enact all sorts of racist, ableist, and discriminatory legislation, such as immigration control and involuntary sterilization. It wasn’t until Germany extended its eugenic practices to include genocide, that the United States began to question its support. The idea that we should eliminate ‘undesirable genetic material’ has not fully gone away and is still used in fields like IVF, where one can terminate a pregnancy of a genetically disabled offspring. At the core of the belief that disabled, chronically ill or fat people should ‘fix’ themselves with food or diet is ableism from discriminatory social movements that exhibit these traits as undesirable.

Ableism and health and wellness

The narrative that certain bodies are undesirable and must be ‘fixed’ has remained a fundamental part of health and wellness culture. It has simply shifted into more socially acceptable forms of discrimination, thanks to the $71 billion weight loss industry. Companies spent more than $1 billion on ads for weight loss and diabetes medicines in 2023. Ozempic alone spent $208 million on ads in 2023, often targeting vulnerable communities like disabled, fat people and women who struggle the most with body dissatisfaction. But the problem doesn’t stop with the predatory mega-corporations in the weight loss industry.

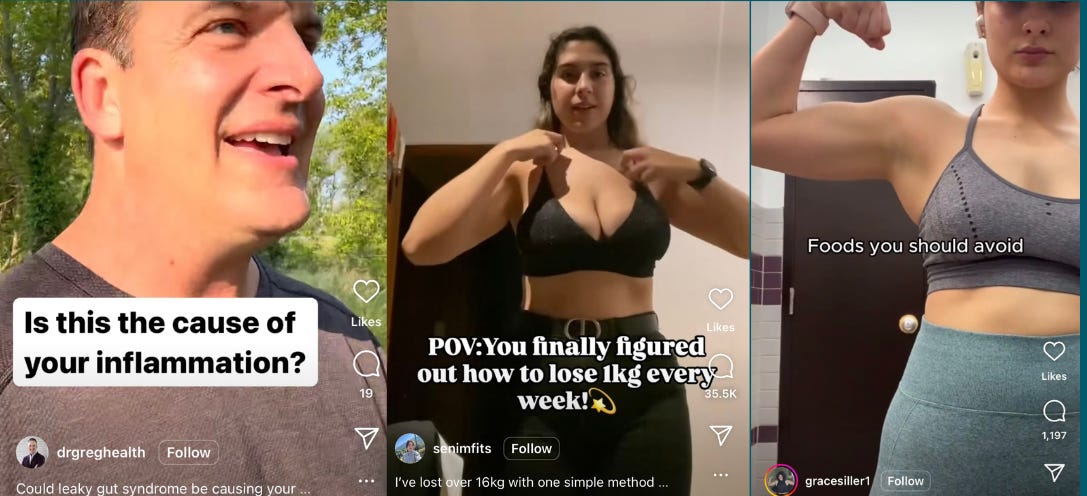

These same ableist, personal-responsibility-focused messages have become an inextricable part of the online fitness industry, which is dominated by able-bodied influencers and ‘personal trainers.’ These influencers are everywhere and have shaped our entire online ‘health and wellness’ culture. Anyone who has ever looked up workout videos online has likely come across one of many fitness-influencer giants, including Kayla Istines, Chris Bumstead or Jessica Bickling. While fitness influencers can provide helpful information and inspiration, their advice is rarely fact-checked and can be misleading and laced with ablelist narratives.

A study from the journal Body Image found that 60% of videos posted by fitness influencers presented misleading or harmful information. The authors explained that the vast majority of videos perpetuated negative messages, including sexualization, body shaming, calorie deficits and excessive dieting. On the surface, these influencers appear to be helpful resources to anyone looking for inspiration and ideas on a fitness journey. They may even have testimonials to show how many people they’ve helped and get thousands of likes and views on every piece of content. But beneath the exterior of shiny abs and overly-trained glutes is a dark, dangerous reality capable of perpetuating deep shame and discrimination in entire marginalized communities.

The truth about fitness influencers

Online fitness influencers rarely have more than a basic personal training certification, if that. Most are not college-educated and lack essential foundational knowledge about the human body, yet frame themselves as ‘experts.’

Online fitness influencers who are not formally educated are not obliged to follow or consider any ethical considerations. While a physiotherapist has ethical codes to follow to ensure clients are not taken advantage of, there are no regulations fitness influencers have to follow.

A fitness influencer can literally promote any information they believe in, even if it has no substantial evidence and can cause harm to their audience.

Most influencers, in lieu of college education and a resume, use their six-pack abs and BBL glutes as the qualifier to show they are the experts they say they are. Having a ‘nice’ body does not mean someone is qualified to provide any sort of nutritional or fitness advice.

Influencers don’t care if you get screwed over by their advice. As long as you spend $75 on their latest unregulated hydration supplement, who cares if you stop your life-saving medication?

Many fitness influencers are scared of modern medicine and are anti-vax, having internalized deeply ableist narratives themselves. The wellness influencer to far-right grifter pipeline is real.

Conclusion

Food is not medicine. While diet and exercise are important for managing many conditions, they cannot cure or erase a disability. The narrative that all disabilities are simply a result of us not doing enough to manage our health is false. Bodies are complex systems affected by many factors. Starting as early as the eugenic movement around WWI, the belief that certain bodies are undesirable has become a foundational part of the modern health and wellness industry. Fitness influencers help perpetuate the belief that health is solely a matter of personal responsibility and that fatness and disability should be avoided at all costs. These narratives directly harm vulnerable communities that may internalize the belief that there is something wrong with their body, and with the right diet and exercise, it can be cured.

All bodies, including disabled and fat bodies, have a rightful place on their earth. We do not need to be fixed, hidden away, or erased. Our bodies hold value and deserve to be accepted, embraced, and treated with personalized, non-predatory care. Disabled bodies are not going anywhere, and we are enough.

💭 Reflection Prompts 💭

Do I blame myself for my body size or disability?

What ableist narratives have I internalized?

Where do I get my health advice from?

Is there someone in my life encouraging me to do all I can to avoid being disabled or fat?

If you feel comfortable sharing, consider leaving your answer in the comments below <3 or, share this article with someone who you think it would help!

—-

If you enjoyed this article, you may want to check out one of my other articles on chronic illness and body acceptance:

Disclaimer: This article is not meant to provide or replace professional health advice. I am not a dietician or medical practitioner. Please consult your healthcare professional before altering your treatment plan.